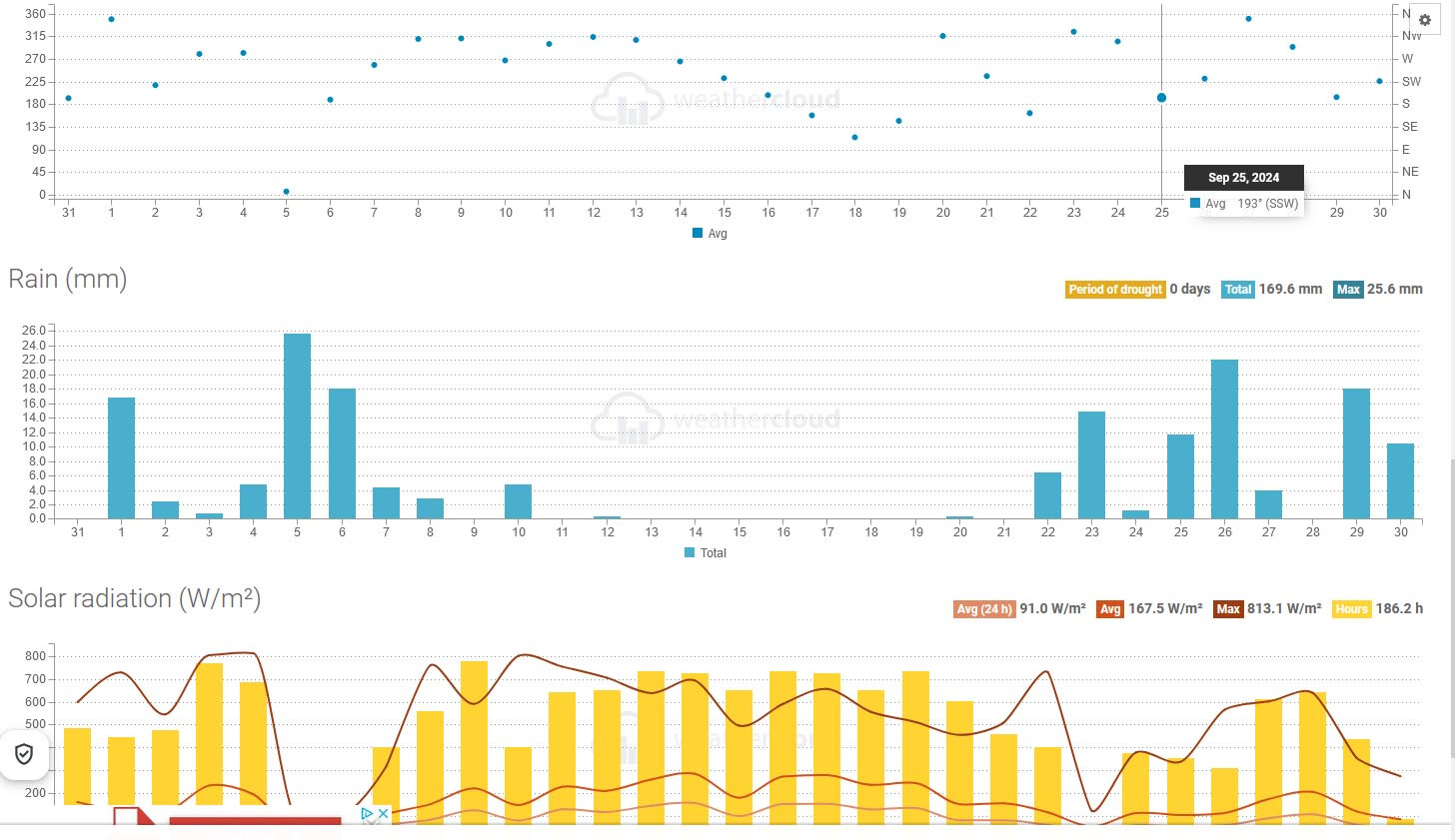

We’ve had more than enough rain in September. My weather station records report that it rained on 19 days with almost 170 mm of precipitation. That’s more than 3 times the monthly average of around 50 mm and 6 rainy days for my area. And as this week’s newsletter lands in your inbox, I will be driving to Clevedon in Somerset to talk about ‘Coping with too much rain.’ How very appropriate!!

It’s been a wet week around the world too. Thanks to Hurricane Helene, a massive 45 inches (1143 mm!!!!!) of water were dumped on the mountains above Asheville, Mississippi causing the city to be flooded and covered in mud. I can’t even begin to imagine what that amount of water looks like. Ironically this city has been listed as a top climate haven city. Clearly, no city is safe from these extreme weather events.

But there’s drought elsewhere. Huge tracts of the Amazon are burning at the moment. Not because of deforestation but drought. And while our summer really didn’t get going, elsewhere peop…